313–323, Constanta, România, Academieii Republicii Socialiste România.Įlston, R. C., 1974, Segregation analysis: An overview, in: Proceedings of the 8th International Biometric Conference, L. A life table approach to analysis of family data, J. C., 1973, Age-at-onset distribution in chronic diseases. B., 1977, Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm, J. N., 1974, The use of additional information in estimating disease risks from family histories, Biometrics 30:655–665.ĭefrise-Gussenhoven, E., 1962, Hypothèses de dimérie et de non-pénétrance, Acta Genet. W., 1953, Regular two-allele and three-allele phenotype systems. 209–266, Plenum Press, New York.Ĭotterman, C. L., 1980, Linkage analysis in man, in: Advances in Human Genetics, Vol. F., 1971, The Genetics of Human Populations, W. 251–298, Plenum Press, New York.Ĭavalli-Sforza, L.

H., 1980, Pedigree analysis of complex models, in: Current Developments in Anthropological Genetics (J. H., 1978, Probability functions on complex pedigrees, Adv. H., DeNevers, K., and Sridharan, R., 1976, Calculation of risk factors and likelihoods for familial diseases, Comp. A., 1977, Ascertainment in the sequential sampling of pedigrees, Clin. C., 1979, Multifactorial genetic models for quantitative traits in humans, Biometrics 35:55–68.Ĭannings, C., and Thompson, E. R., 1964, An analysis of transformations, J. J., 1961, Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Genetic Linkage, Oxford University Press, London.īatschelet, E., 1963, Testing hypotheses and estimating parameters in human genetics if the age of onset is random, Biometrika 50:265–279.īox, A. J., 1951, A classification of methods of ascertainment and analysis in estimating the frequencies of recessives in man, Ann. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.īailey, N. These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. In the first section, the various models are defined mathematically so as to give precision to the assumptions that are made, and the genetic implications of these assumptions are discussed. Therefore, on the assumption that appropriate computer programs will soon be widely available, this review will pay more attention to the statistical principles involved, and less to methods of computation. The fast development of the subject in recent years can be largely attributed to the increasing availability of electronic computers, allowing the use of sophisticated analyses that would otherwise be impossible. There have been many reviews of the early literature on this topic (see, e.g., Smith, 1956, 1959 Steinberg, 1959 Morton, 1962, 1964, 1969 Elandt-Johnson, 1974), and this will not be repeated here rather the present chapter will concentrate on the developments in this area over the last decade, incidentally pointing out how the earlier methods can be considered as special cases of the more general theory that is now available. More generally, we can define segregation analysis as the statistical methodology used to determine from family data the mode of inheritance of a particular phenotype, especially with a view to elucidating single gene effects it is thus a basic tool in human genetics. It shows the name and status of the user.The statistical detection of Mendelian ratios in human sibships has long been known as segregation analysis. Let’s assume that in our application we have the following view: In other words, it’s better to have more but smaller interfaces than one large one.

Today we will be dealing with the Interface Segregation Principle 🙂 Interface Segregation PrincipleĪs you can see in the picture – customers should not be forced to rely on interfaces that they do not use.

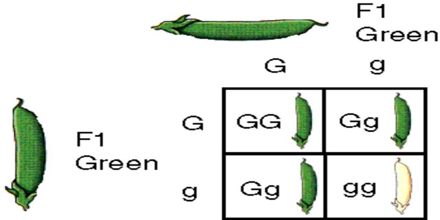

PRINCIPLE OF SEGREGATION CODE

It is a set of rules thanks to which we can write code that will be easier for us to scale, and change the behavior of our application, without moving the code of a large part of the app.

PRINCIPLE OF SEGREGATION SERIES

This is the fourth article in the series on the acronym SOLID.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)